Stamping coins as a form of itinerant propaganda in the Flavian Age of Imperial Rome

Empires do not take shape peacefully. Rome’s territorial holdings were no exception, being principally won through years of imperialist warmongering. To commemorate its martial victories, the Roman state minted coins stamped with designs evocative of triumph and conquest. Such images were of the utmost importance to the realpolitik of emperorship, disseminating on a near-industrial scale the soldierly qualities of the ruler [Christopher Howgego, Ancient History from Coins (London: Routledge, 1995), 67–70; Carlos Noreña, Imperial Ideals in the Roman West: Representation, Circulation, Power (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 190]. From the reign of Augustus (r. 27 BCE–14 CE) onwards, coins of the Principate typically featured the profile of the emperor or another member of the ruling house as their obverse types [Reinhard Wolters, “The Julio-Claudians,” in The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Coinage, ed. William E. Metcalf (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 340]. Reverse faces exhibit greater variability, including the motif of the captive barbarian.

“The Roman state minted coins stamped with designs evocative of triumph and conquest

Here I will examine a small number of coins produced under the Flavian emperors, all of which assimilate peregrine war captives (captivi) into their iconographic scheme.

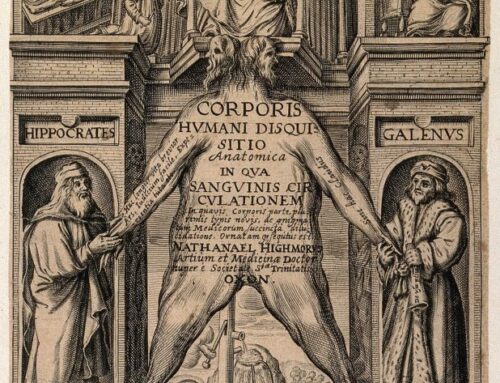

Let us begin with a bronze sestertius minted in the city of Rome around 71 CE (see fig. 1) [Harold Mattingly, Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum (London: Oxford University Press, 1930), Vol. 2, 185, no. 761]. Struck as part of Vespasian’s (r. 69–79 CE) Judaea capta series, the coin memorialises the emperor’s vanquishment of the Jewish revolt, depicting a standing male captive and a Jewess, the latter personifying the subjugated province of Judaea. Separated by a date palm tree – emblematic of the Jewish defeat – the prisoner of war’s hands and neck are clearly enchained, while Judaea herself is represented slumped against the palm’s trunk, her grief-wracked face supported by her left arm [For the significance of the date palm motif, see Johannes Nussbaum, “Palm Trees and Palm Branches in Graeco-Roman Iconography: Why the Palm Trees on Judaea capta Coins are a Symbol for Judaea,” Historia 20, no. 4 (2021), 463-493]. Although impossible to substantiate, the effigy of the Jewess may also insinuate the fulfilment of a prophecy documented in the Hebrew Bible, where the sacked city of Jerusalem is personified as a despoiled woman collapsed on the ground [For a translation of the relevant passage, see Moisés Silva, “Esaias,” in A New English Translation of the Septuagint, ed. Albert Pietersma and Benjamin G. Wright (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 828]. Both figures are margined by a trove of armour, including a helmet, cuirass, and two round shields. Crowning the reverse is emblazoned the legend IVDAEA CAPTA. Written in the ablative absolute, the inscription might be translated as “when Judaea was captured,” or “on the occasion of the defeat of Judaea.”

Figure 1. Reverse of bronze sestertius minted in 71 CE. Property of the British Museum (inv. no. R.10656).

Vespasian’s eldest son Titus (r. 79–81 CE) continued his father’s tradition of numismatically celebrating the Roman victory over the Jewish rebels. Having commanded the legions during the siege of Jerusalem, Titus had good reason to promote his military competencies. A gold aureus minted in 80 CE depicts a trophy of arms between two seated captives (see fig. 2) [Mattingly, Coins of the Roman Empire, Vol. 2, 230, no. 36]. The right facing male prisoner is again rendered with his hands tied behind his back, though, unlike the above sestertius, the man is visibly naked. Reminiscent of the personified Judaea of Vespasian’s coinage, the female captive is shown dejectedly leaning forward, her head propped up by her left arm. An abridged legend endorsing Titus’ political attainments garlands the composition: TR P IX IMP XV COS VIII P P (Tribunicia Potestate Nona, Imperator Quintum Decimum, Consul Octavum, Pater Patriae).

Figure 2. Reverse of gold aureus minted in 80 CE. Property of the British Museum (inv. no. 1908,0110.2651).

Having not served in Judaea, Domitian (r. 81–96 CE), the younger son of Vespasian and Titus’ heir, lacked his predecessors’ claim to military aggrandisement. Seeking to undergird his imperial authority with victory on the battlefield, Domitian embarked upon a lightning campaign against the Germanic Chatti. Decried by the historian Tacitus (ca. 56–120 CE) as a “mock triumph” (falsum triumphum), the supposed victories of Domitian were elaborately celebrated in Rome, including with the striking of honorary medallions and coins [Tacitus, Agricola, 39.2]. The captive motif once again featured as the reverse type on a bronze sestertius issued in 85 CE (see fig. 3) [Mattingly, Coins of the Roman Empire, Vol. 2, 369, no. 325]. Echoing the composition of past dies, two figures are represented: a crestfallen woman and a standing male prisoner, the former embodying Germania herself. A trophy of arms separates the pair, with the legend GERMANIA CAPTA surmounting the arrangement. Similar to the feminised Judaea, the depiction of Germania as a mourning woman served to underscore Rome’s martial primacy, emasculating the vanquished population [Davina Lopez, Apostle to the Conquered: Reimagining Paul’s Mission (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2008), 37].

Figure 3. Reverse of bronze sestertius minted in 85 CE. Property of the British Museum (inv. no. R.11329).

A more complex design can be observed on a silver medallion issued the same year (see fig. 4) [Mattingly, Coins of the Roman Empire, Vol. 2, 316, no. 83]. The goddess Minerva is seated left of centre on a throne, her feet resting on a footstool. In her outstretched hand is balanced the goddess Victory, and in the crook of her right arm lies a transverse sceptre. Below Minerva’s throne can be seen the outline of a riverboat, within which sits a prisoner of war, his hands bound together at the wrist. The image of a captivus being transported by water calls to mind the slave trade, a doubtlessly intentional allusion. Indeed, Tacitus reports the conveyance of enslaved Germans across the Rhine in the age of Domitian [Tacitus, Agricola, 28.3]. An abbreviated legend honouring the emperor’s political credentials brackets the relief: IMP VIIII COS XI CENS POT P P (Imperator Nonum, Consul Undecimum, Censoria Potestate, Pater Patriae).

Figure 4. Reverse of silver medallion minted in 85 CE. Property of the British Museum (inv. no. R.13010).

We come now to the question of othering, understood here to refer to those strategies of boundary making purposed to differentiate insiders from outsiders. Manifestly, in detailing war captives on the reverse face of coins, ancient die engravers sought to transmit the idea of Rome’s military supremacy over the barbarian [Annalina Caló Levi, Barbarians on Roman Imperial Coins and Sculpture (New York: The American Numismatic Society, 1952), 3]. The otherness of foreign prisoners was emphasised in a variety of ways. For instance, male captives were represented as naked or with facial hair, a decidedly un-Roman hallmark during the Flavian period. Legends too helped communicate the alterity of the barbarian, with the capta inscriptions of figures 1 and 3 drawing an overt ethnic link between the manacled prisoners and subjugated territory.

Yet, as Liv Mariah Yarrow underlines, in a society where slaveholding was extensively practised, the Roman display of bodies was not only metaphorical [Liv Mariah Yarrow, The Roman Republic to 49 BCE: Using Coins as Sources (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 110]. Prisoners of war, lest we forget, constituted a major source of unfree manpower during the late Republic and early Principate [Walter Scheidel, “The Roman Slave Supply”, in The Cambridge World History of Slavery, Volume 1: The Ancient Mediterranean World, ed. Keith Bradley and Paul Cartledge (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 294-297]. The othering of war captives in numismatic designs hence parallels the stigma of alienness experienced by servi novicii (new slaves) more generally. As a form of itinerant propaganda (travelling from hand to hand), it is tempting to wonder if the motif of the captive barbarian ever influenced popular attitudes towards enslaved war captives? And relatedly, how might a slave deracinated in Judea or Germany have felt upon seeing their likeness portrayed on the reverse of coins? Such questions have no certain answer. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to postulate that the othering of war captives in Flavian coinage was a deliberate artistic choice, intended to simultaneously debase the barbarian and glorify the emperor’s victories.